Imagine taking off from a runway like a normal aeroplane but flying so high and so fast that when you unclip your seatbelt, you float around the cabin. Look out of the windows: on one side is the inky blackness of deep space, while on the other is the electric blue of your home planet, Earth.

This is no joyride for a few brief minutes of space-tourism weightlessness. Instead you are three, five or even 10 times higher than those little hops. In front of you is your destination: a space station. Perhaps it is a hotel or a place of work. You are in low earth orbit - and you've got there in far less time than it takes for a transatlantic flight.

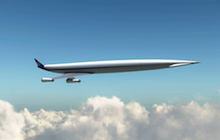

This is the promise of the spaceplane, and it took a step closer to reality yesterday. UK Minister for Universities and Science David Willetts confirmed the government's £60m investment in Reaction Engines Ltd.

Spaceplanes are what engineers call single-stage-to-orbit (if you really want to geek out, just use the abbreviation: SSTO). They have long been a dream because they would be fully reusable, taking off and landing from a traditional runway.

By building reusable spaceplanes, the cost of reaching orbit could be reduced to a twentieth current levels. That makes spaceplanes a game changer both for taking astronauts into space and for deploying satellites and space probes.

If all goes to plan, the first test flights could happen in 2019, and Skylon - Reaction Engines' spaceplane - could be visiting the International Space Station by 2022. It will carry 15 tonnes of cargo on each trip. That's almost twice the amount of cargo that the European Space Agency's ATV vehicle can carry.

Traditional rockets can only reach orbit by dropping off empty fuel tanks as they go. This makes them virtually impossible to re-use because even if you could collect all the parts, they would need so much refurbishment and reassembly that it's usually quicker, easier and cheaper to build new ones.

Rockets are cumbersome because not only must they carry fuel, they also need an oxidising agent to make it burn. This is usually oxygen, which is stored as a liquid in separate tanks. Spaceplanes do away with the need for carrying most of the oxidiser by using air from the atmosphere during the initial stages of their flight.

This is how a traditional jet engine works, and making a super-efficient version has been engineer Alan Bond's goal for decades. In 1989, he founded Reaction Engines and has painstakingly developed the Sabre engine, which stands for Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engines.

In late 2012, tests managed by the European Space Agency showed that the key pieces of technology needed for Sabre worked. No one else has managed to successfully develop such a technology.

This makes Sabre a world-leading technology and the new money will allow a full-size prototype to be made as a final test before commercial production can begin.

To reach orbit, Skylon will use Sabre to boost it to Mach 5. It will then close the air intakes and use a small amount of onboard oxidiser to turn the jets into rockets and boost itself to Mach 22. At this speed, roughly 7.5km/s, the craft will reach low earth orbit.

Used terrestrially, an aeroplane powered by Sabre engines could whiz you from the UK to Australia in just four hours, the same time it takes holidaying Brits to reach the Canary Islands.

Spaceplanes should not to be confused with space tourism vehicles such as Virgin Galactic's Space Ship Two. The highest altitude this vehicle will reach is about 110km, giving passengers about six minutes of weightlessness as the craft plummets back to Earth before the controlled landing.

Although there is no fully agreed definition, space starts at around 100km in altitude. To have any hope of staying in orbit, you would have to reach twice that altitude. The International Space Station orbits at 340 kilometres, whereas the Hubble Space Telescope sits at 595 kilometres.

On the Reaction Engines recruitment web page, the company offers potential employees the chance to "join the organisation that will conceivably have the biggest impact on the aerospace propulsion industry since [inventor of the jet engine] Sir Frank Whittle's original design."

I think that might actually be an understatement. The Sabre engine could open up our access to space as never before.

Stuart Clark is the author of The Day Without Yesterday (Polygon). Find him on Twitter as @DrStuClark

0 comments Blogger 0 Facebook

Post a Comment